Northern gliders linking OSNAP and Vitals

Brad deYoung, Jaime Palter, Ralf Bachmayer, Robin Matthews, Tara Howatt, Brian Claus – Memorial and McGill Universities

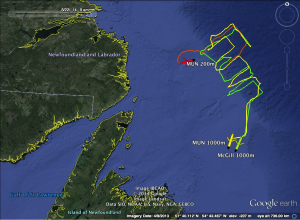

At Memorial we are active not only in OSNAP, but also in Vitals a different program with a focus on air-sea gas exchange in the Labrador Sea. So a sibling program to OSNAP. This year is still preparation for the main field season next year in 2015. We wanted to deploy the three gliders this year to explore the along-shelf variability of the cross-shelf character of the Labrador Current at the shelf-break, to learn more about flying multiple gliders at once, to gain more experience with the 1000m glider and learn more about new gas sensors. We were also very excited to link our two programs by flying the gliders along the shelf-break through the 53 o N mooring array.

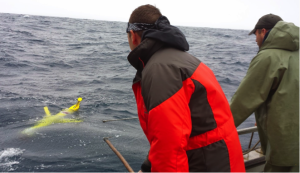

Our gliders went out in early July. Our plan was to deploy the three gliders and have two criss-crosses the shelf break, surveying the shelf-break Labrador Current, while the third glider sampled inshore on the inner side of the current. This did work, but not quite as well as we had planned.

The deployment was from CSS Hudson for which we thank our colleagues Blair Greenan and Dave Hebert at the Bedford Institute of Oceanography. This was the same cruise on which the Canadian OSNAP moorings were deployed. The zigzag plan did mostly work but we had to recover one glider early because of a leak problem and the others had some troubles with lighter than expected water at the surface on the shelf. The gliders were in the water for about six weeks, about four weeks short of our intended deployment.

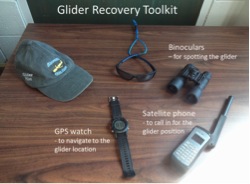

Beyond some cool data, that we are now looking at, we learned some things about flying multiple gliders in strong currents, we improved our IPad App that allows us to monitor the gliders, and we learned some new things about gliders behaviour. As it turns out, if the glider is coming to the surface but is a little too heavy and so only makes it to 7 m depth (that is not really very good, no surfacing no communication no GPS fix) then the glider is happy and does not conclude that there is a big problem. So it does not get upset and drop its emergency weight to force its way to the surface. Our two heavy-weight gliders did eventually conclude there was a problem, but for another reason, and dropped their weights. We then had to arrange a ship to head out to the shelf break to pick up the gliders turned into surface drifters. The good news is that glider recovery does not require a hugely complicated set of instruments (see picture) and fishing boats are pretty much perfect for the task and fishermen are very good at finding and retrieving things on the ocean.

As it turned out, the weather cooperated and we had good positions, and so the recovery went very smoothly. We did also try to recover another lost instrument, an Ocean Bottom Seismometer, deployed by our German colleagues and adrift with two years of data inside but we were unable to find it as the Argos positions were too stale or inaccurate and we just could not find it. That was very frustrating. We knew where it was but not well enough to find it. The good news for our gliders is that in finding them they still had lots of battery power left and so after a little refurbishment they were ready for another deployment. You can’t hold a good glider down, or up – what is that expression? More on the second deployment in our next blog entry.