by Nora Fried and Patricia Handmann

Today this blog is focusing on one of the central Instruments of almost all oceanographic cruises: the CTD – Conductivity-Temperature-Depth sensor. One of the interests in oceanography is on the physical, chemical and biological properties of seawater. Most oft the work on board is accumulated around the CTD schedule. The CTD we use on this cruise went on around 70 dives until now, but what exactly is a CTD?

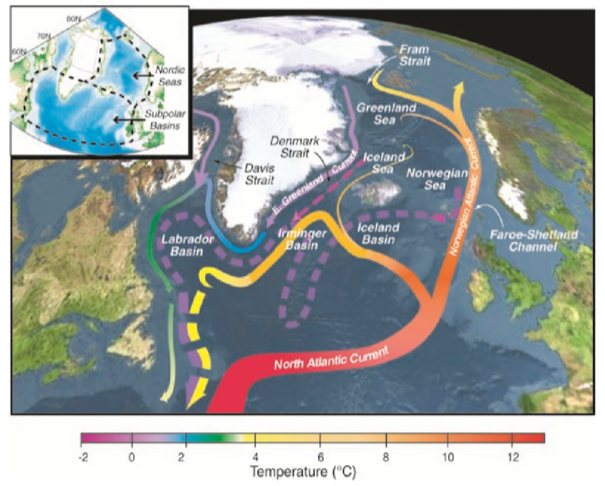

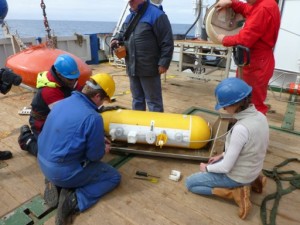

A CTD-rosette consists of a metal cage with a centrally installed sensor pack – the CTD. These sensors are measuring conductivity, temperature and pressure in real time being consistently pumped while passing through the water column. Salinity can be computed from conductivity, temperature and pressure. The maximum depth this instrument can resist is around 6000m. Since our cruise is passing through Labrador and Irminger Sea our deepest station until now is around 3800m deep.

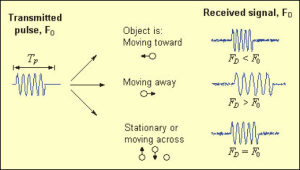

Furthermore there are up to 24 Nisken water sampler bottles, which can hold up to 12 liter of seawater and bring them up to the surface. Additionally to the CTD sensors and the water sampler bottles we installed some more sensors on the CTD this cruise: we measure oxygen concentration, fluorescence, velocity of the surrounding water, distance to the bottom light penetration depth and the turbidity.

The whole CTD-rosette is mounted on a wire, which is connected to the vessels winch system to veer out the instrument into the water and heave it back to the deck. The wire is a cable at the same time and makes real time data transmission from the sensors to a computer on board possible. So temperature, salinity and pressure of the surroundings can be monitored the whole time.

Once a CTD Station is reached and the instrument is prepared the rosette can be deployed. Before deploying the bridge has to approve of the action, then the winch driver is informed by the CTD watch that the instrument can be deployed. The instrument is then veered out with a velocity of around one meter per second – so the CTD watch has to observe the altimeter and all the other instruments the whole time in order not to hit the ground.

Due to different properties of seawater in different depths, density oft the surrounding water is changing and the CTD is drifting with the currents – the pressure is different to the length oft the veered out rope. Therefore the winch is stopped at a depth of 10 to 15 meters to the ground in order not to hit the ground with the sensors. Once the instrument has reached the full depth the first water sampler is closed and the instrument is heaved back up to the surface and the sampler bottles are closed on different depths by the CTD watch.

Once the Instrument is back on deck, secured by ropes and washed, the work of the chemists and biologists starts. They take oxygen and nutrient samples and are the firsts to touch the sample bottles. When all samples are taken its time for the CTD watch to take salt samples – therefore sample bottles are filled and measured by a salinometer. Measuring the same properties with different measuring techniques can reduce the overall error.

Depending on the water depth the duration of a CTD cast can vary greatly. A station takes particularly long time if calibration or testing of additionally installed instruments is performed on the CTD rosette. Especially instruments that will be deployed on multi-year moorings need to be tested and calibrated before final deployment. Little CTD Systems called MicroCats are tested as described above. MicroCats measure temperature, conductivity and pressure just like the system installed on the rosette. In order to mount them on the rosette some sample bottles from the rosette are replaced by the MicroCats, and the CTD profiles of the rosette system gets compared to the Microcat profiles to calibrate after the cast. In order to get good calibration values, bottles are closed at five different depths with preferably constant salinity and temperature during the up-cast. For these depths the CTD is stopped for five minutes. Salinity of the sample bottles is determined by a salinometer and compared to the MicroCats-data afterwards. Moreover, the releasers of a mooring have to be tested for reliability before deployment. The releasers are activated by a specific hydrophone signal. These tests are essential to be able to recover the moorings with all the instruments after multiple years. Though a calibration-CTD takes longer, it provides some diversion during a CTD-watch and all in all we like our ‘Micro-Cats’.

In order to run the CTD around the clock, we are working in shifts of 4 hours at a time. At midnight the middle watch begins during which, one usually has some peace and quiet as most people on the ship are sleeping. To be regularly on deck at 2 a.m. and watch snowfall at night or the bright summer night sky at the Greenland coast is also an advantage of this shift.

A notably nice shift follows from 4 a.m. to 8 a.m. when sun is rising. A sunrise can be impressively beautiful at sea, appearing different every morning.

The 4 to 8 shift is then replaced by the so-called retirement shift from 8 a.m to 12 a.m. This shift is very close to a normal day.

Three to four students take care of the CTD during their watch time. This watch system is kept during the whole cruise and can make one sleep a lot during daytime. Also an ostrich steak with asparagus can happen to be your breakfast.

We already had rough weather during this cruise: nearly 7 meters of waves and around 34 kn of wind brought adventures like sliding through the CTD lab on a chair or not secured things on waltz to our trip. Even through these kinds of weather conditions the Maria S. Merian is able to perform CTD casts in a safe way. The sailors and the bridge show special skills and repeatedly perform extraordinary in order to bring the CTD-rosette back to deck without harming it.

Sometimes it also happens that something goes wrong during a CTD-station – Sensors stop working or seawater finds its way entering plugs or cables. Then it is time for error analysis by our CTD technicians. As soon as the CTD-rosette arrives on deck the troubleshooting starts.

Up until now we have had a successful and smooth cruise and hope to continue that way until Reykjavik.

Very hearty greetings from the dog watch der MSM54