by Laura Castro de la Guardia

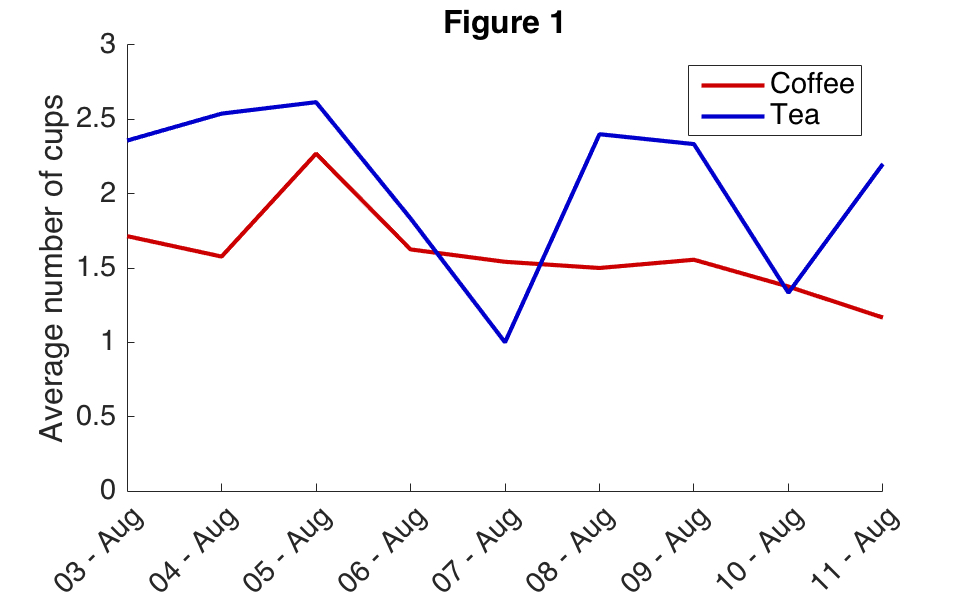

When I am ask by friends: What is it that I study? I generally give them the quick answer: I study biological-oceanography at the University of Alberta. But when they look-up “University of Alberta” on Google map for example (Figure 1), they always point out: there are no coastlines near the University of Alberta! In fact, the province of Alberta in Canada, has NO coastlines at all. So, how is it then, that I can study the oceans? Although one way will be to spend a lot of time travelling to either western, eastern or northern Canada to do my field work, I can also study the oceans from my own desktop at university!

I use a mathematical model on the computer to create a virtual ocean with some biology and chemicals; it is sort of like a video game, but the model attempts to be as realistic as possible. The core of the model is based on the most current understanding of physical and mathematical relationships that exist between the ocean, the atmosphere, the sea ice and the biology.

There are many models available. The ocean model I used is called NEMO (http://www.nemo-ocean.eu/) that comes together with a sea ice model LIM. The biological and chemical model I used is embedded within NEMO and it is call BLING (https://sites.google.com/site/blingmodel/). Cool names acronyms, right?! Both models are free to use by any user, but it requires some understanding of computing science, programing, and a very powerful computer. We have to run our model on super-computers that are shared across Canada (Compute Canada/Calcul Canada).

Unlike what you may have imagined from my video game analogy, the output of the model is not a movie, but lots of numbers (a.k.a simulated data). The “simulated data” is what I use to do statistical analysis of many different things, for example, I can see the current state of the ocean, or the sea ice, or the marine algae (phytoplankton). We can also make movies with the simulated data (e.g. http://knossos.eas.ualberta.ca/vitals/outcomes.html)

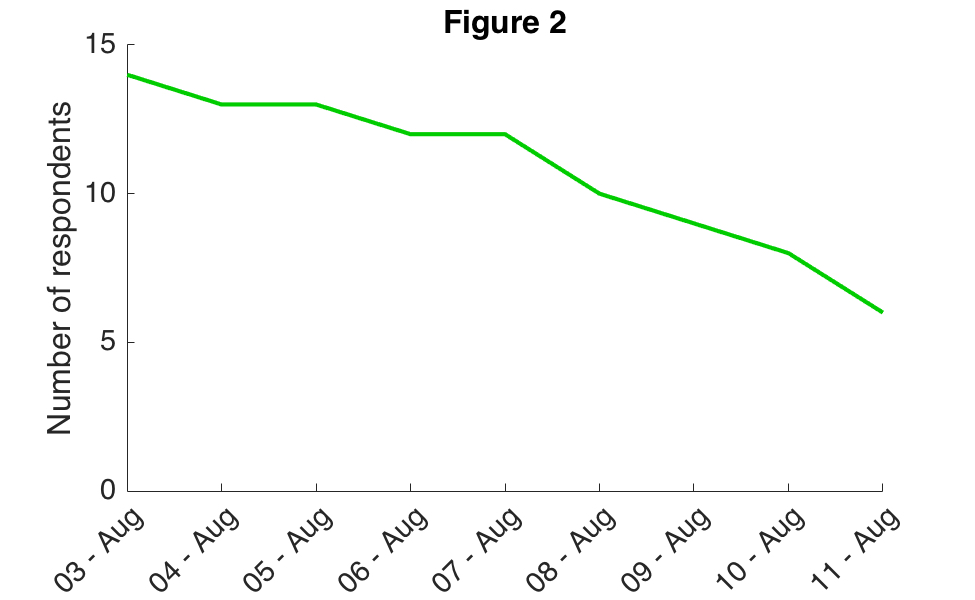

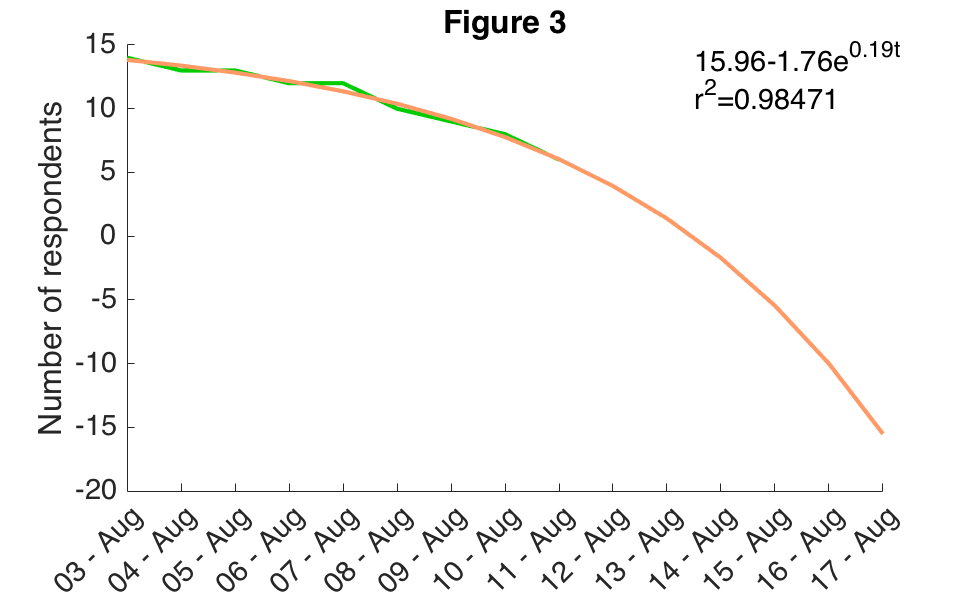

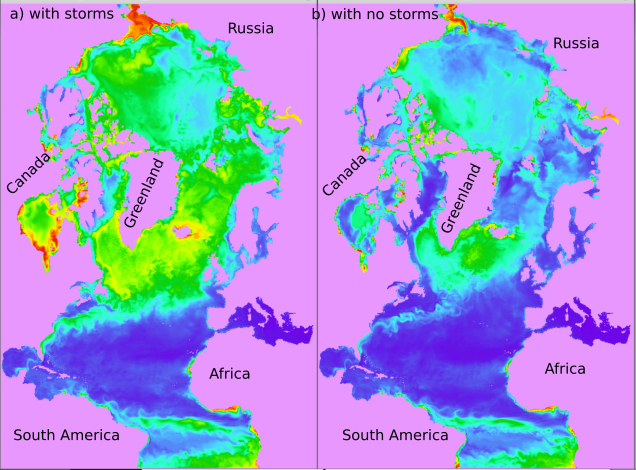

Although models are still not able to reproduce an identical ocean to our real ocean, one of many advantages of an ocean model is that I can study how one single event/phenomena/or property in the atmosphere affects my simulated ocean or biology. This type of studies are called sensitivity studies, and they are like experiments in a lab. This is important because in our current climate, many things are changing at once (for example in the Arctic Ocean, sea ice is decreasing, temperature is increasing, the rate of river flow into the ocean is larger, there is more rain, there are more storms during the autumn), but we only observe the response of the oceans to all changes. While with the model I can have the response of the model to all changes, but also the response of the phytoplankton to only one change (e.g. more storms during fall (Figure 2)). Depending on what I am studying, I can then answer which of all these changes is the most important, which one is the one I should be most concern with? These are the kind of questions I would like to focus on for my sensitivity experiments, because these questions can help us prepare for the changing future: e.g. they could help shape or guide the adaptive tactics and conservation programs.

Figure 2. A simulation with storms (a) compared to a simulations without storms (b). The differences between each panel shows the regions where the storms have a greater impact on phytoplankton.