Dear colleagues,

We are pleased to invite you to submit an abstract to the session: Variability and controls of ocean climate revealed by long-term multidisciplinary eulerian observatories that we have prepared at the next AGU Falll Meeting, which will take place on 12-16 December 2022 in Chicago (in person and virtual participation).

The deadline to submit your abstract is *3 August (23:59 EDT/03:59 GMT)*, instructions are found here.

We hope to meet you virtually or in person in December. Please don’t hesitate to forward this call to other colleagues who may be interested.

Raquel, Elizabeth, Yao and Dariia

*OS026 – Variability and controls of ocean climate revealed by long-term multidisciplinary eulerian observatories*

The global ocean absorbs, stores, and redistributes vast amounts of heat and carbon and is therefore the main driver of climate regulation. It means that human-induced forcing is superimposed on ocean natural variability, and that this variable forcing involves complex interactions and feedbacks of physical, chemical and biological processes from the air-sea interface to the sea-floor. To understand these complex relationships between ocean processes, their forcings, and effects, long term time-series of Essential Ocean Variables (EOV) from fixed point (Eulerian) multidisciplinary observatories, monitoring processes that take place over much shorter periods of time, are critical.

In this session, we aim to share most recent research based on long term OceanSITES data sets or on long term time-series from eulerian multidisciplinary observatories not included in the network addressing air/sea exchange processes such as heat and freshwater fluxes, and ocean carbon and oxygen update; ocean transport, but also other biogeochemical, biological, and deep ocean processes. We welcome contributions which describe ocean variability at different time-scales from large-scale climatic fluctuations to hurricanes, and examine their governing mechanisms and environmental implications. Submissions focused on processes-oriented studies integrating different observing platforms (e.g. satellite, Argo floats, gliders, …) with long-term eulerian observation (moorings, ship-based time-series) are also encouraged as well as studies combining observations and modelling.

*Conveners:*Raquel Somavilla (Spanish Institute of Oceanography), Elizabeth Shadwick (CSIRO Marine and Atmospheric Research), Yao Fu (Georgia Institute of Technology), and Dariia Atamanchuk (Dalhousie University)

*Index Terms: *4215 Climate and interannual variability, 4805 Biogeochemical cycles, processes, and modeling, 4504 Air/sea interactions, 4532 General circulation

Author Archives: Yao Fu

Call for Abstracts: AGU Fall Meeting Session “OS026 – Variability and controls of ocean climate revealed by long-term multidisciplinary eulerian observatories”

OSNAP GDWBC 11 July 2022

By Ellen Park

Life at sea is organized chaos.

Each day is incredibly valuable because sea time is so expensive.

As a result, prior to stepping foot on the boat, we had a detailed schedule outlining what operations, like mooring recovery/deployment or a CTD cast, would be completed on each day and their duration in a set order. But this order wasn’t really “set.” It was more realistically the ideal order of operations, assuming no major setbacks. Ultimately, forecasted weather and instrument malfunctions required us to be flexible, forcing us to prioritize certain operations over others due to factors like local conditions, limits on deck space, or transit time to stations.

To keep track of all these moving pieces, everyday a plan of the day (POD) was outlined by the chief scientist, Sheri White, for the upcoming workday. Conversations both amongst the science party and between the science party and the ship’s crew were essential for ensuring that all operations were conducted safely and smoothly and that both scientific agendas for OSNAP and OOI were met.

While the POD often changes multiple times (five times within one day once because of weather!), there are some aspects of life at sea that are constant.

Typically, most days start bright and early at 6am to prep the deck for a mooring deployment/recovery operation or preparation of the rosette for a CTD cast. After breakfast, mooring deployment/recovery or CTD casts begin. Mooring operations last anywhere from 2-6+ hours, depending on the height of the mooring and number of instruments attached. CTD casts on this cruise typically were 2-3 hours and went to 2,000-3,000 meters depth. Depending on the duration of the morning operation, we would break for lunch and afterwards continue or start a new operation. Occasionally, we conduct a few late night CTD casts after dinner, but for the most part all operations are complete by 18:00.

To help stay sane and entertained, people participate in a variety of evening activities after operations are completed. Some people workout in the onboard gym. Others read, play card games, or watch TV/movies in the lounge.

With the end of the cruise approaching, it is exciting to celebrate the accomplishment of achieving all the OSNAP and OOI objectives, despite the weather-related setbacks we encountered. This could not have been possible without the hard work from everyone on the ship’s crew and members of the science party. As we begin our transit to Reykjavik in the upcoming days, I know that I am looking forward to returning to land, but, at the same time, I will be a bit sad to leave the R/V Armstrong.

Posted in Cruises

OSNAP GDWBC 07 July 2022

by Ellen Park

On our eight-day transit to the Irminger Sea, we completed a few calibration casts for instruments that will be deployed on the OSNAP moorings and saw some pretty incredible sunsets (see Figure 1).

Once we reached our target region, we got to work right away. First, we deployed all of the new components of the OOI Global Irminger Sea Array, which consists of a surface mooring, three subsurface moorings, and gliders. Then we moved on to recover the OSNAP Greenland Deep Western Boundary Current (GDWBC) moorings, which are all subsurface moorings. One of the key differences between the OOI and OSNAP moorings is how collected data are stored and recovered. OOI data are stored locally and also telemetered so that data can be accessed by the public in near real time. OSNAP data, on the other hand, are stored locally and cannot be accessed until the sensor is recovered and the data are downloaded.

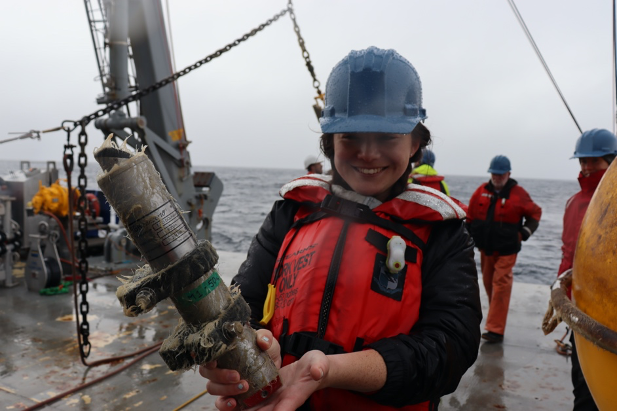

Before recovering each mooring, we do a CTD cast roughly 0.5 nautical miles away from the mooring to provide an endpoint for each timeseries (see Figure 2). Not only can sensors drift overtime, but they also can become biofouled, which will affect the measured value (see Figure 3). Having an endpoint value is important because it allows us to correct the sensor data for these phenomena and provide more accurate results.

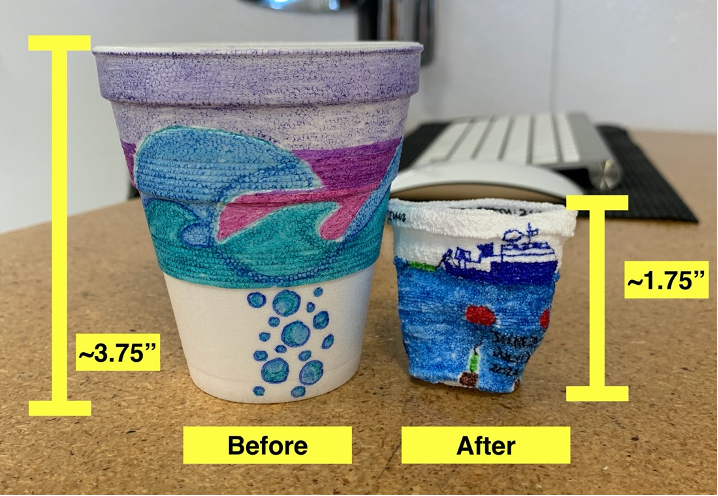

Many of the casts that we have done so far went below 2,000 m depth because we are interested in the GDWBC. Sensors deployed at these depths must be able to withstand harsh conditions and extremely high pressures. 10 m of water is roughly equivalent to 10 decibar of pressure (~1 atm). Therefore, at 2,000m depth, sensors experience 200 times the pressure that they experience at the surface. We could see the pressure effects on Styrofoam cups that we sent down with one of the deep CTD casts (see Figure 4).

We have roughly another week to finish up all of our operations before heading to Reykjavik, where we will leave the ship and fly home. During this time, we will finish recovering and deploying moorings and taking a preliminary look at the recovered two years’ worth of data!

Posted in Cruises

OSNAP Greenland Deep Western Boundary Current (GDWBC) 01 July 2022

by Heather Furey

It’s been a minute. The sun is shining, it is a perfect July day on the Irminger Sea. After an eight-day transit, some amount of CTD casts, some amount of CTD sensor diagnostics, some amount of moored instrument calibrations, and a few glider deployments, we are finally getting to the guts of the work: the mooring deployments and recoveries.

It’s day 12 of 28. We are interweaving the OOI and OSNAP mooring operations. It’s a workload that is in flux; we are up to ‘Plan C’ right now. Plans have changed due to weather days, both the good kind and the bad kind, and a glider recovery. The general plan is to deploy OOI moorings first, as we need to get the deck cleared of equipment before we will have space to recover a similar amount of gear. After OOI moorings are deployed, we recover and then deploy OSNAP moorings, and once done, we recover OOI moorings. That’s the idea, though Plan C has some deviations on that generalized plan. We have 2 out of 16 mooring operations complete so far.

Meanwhile, the galley staff keep cranking out great food, the crew are awesome as always, and we steam along from work task to work task, checking things off the list.

More later, Heather

Posted in Cruises